Graph Traversal

Principles:

- Isolate the algorithms from the data structures they operate on.

- Explicitly state the hypotheses under which an algorithm works. And build up bridges toward satisfying those hypotheses.

In this chapter, we will introduce graphs and a graph traversal algorithm. We will keep it as simple as possible since the concepts here are well-known with rich literature.

{: width="400" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

{: width="400" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

- Graph and Graph Representation

- [A] Graph Traversals -- [M] Explicit graph

- BFS

- Iterative

- Independent of the model

roots(); next() - OnEntry callback --> See another blog entry for a more generic version

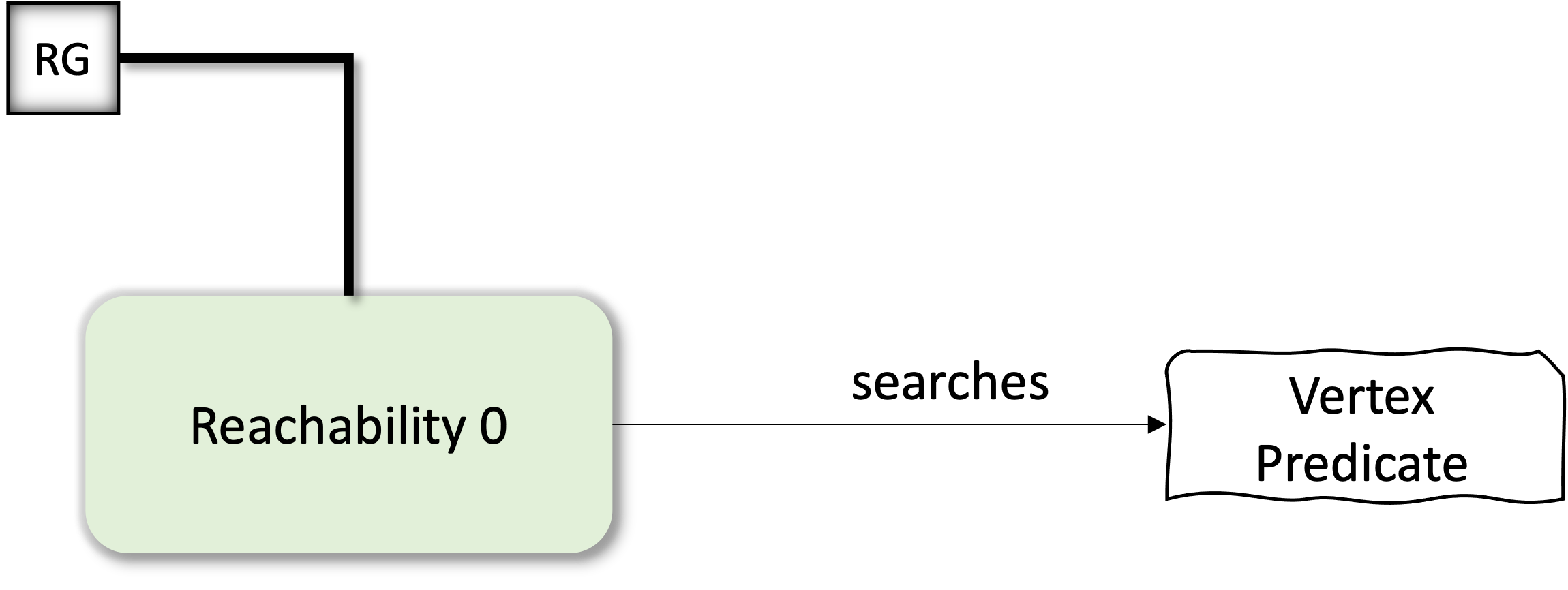

Introducing the Rooted Graph

Graphs are among the most versatile and expressive structures in computer science. They naturally capture a wide range of relationships: from links between websites, to connections in a transportation network, to dependencies in a software project. However, while graphs are powerful, traversing them—systematically exploring their structure—is far from trivial.

One key insight in building robust traversal algorithms is recognizing that how a graph is represented should not affect the traversal logic. In other words, our algorithms should not be entangled with specific data structures. This separation of concerns is not just a matter of good software engineering—it is essential if we want our tools to scale across domains, adapt to new applications, and support multiple input formats.

Yet, there's a more fundamental problem. In many real-world cases, we're not simply interested in an arbitrary traversal of a graph. We want to explore a particular part of it, starting from certain points of interest and systematically branching out. This requirement naturally leads us to a structure that we call a rooted graph.

A rooted graph is not just a graph, it is a graph together with a distinguished set (or multiset) of roots. These roots represent the starting points of traversal. They might correspond to known initial states in a system, entry nodes in a program's control flow, or nodes we suspect are critical in a network. By explicitly incorporating the notion of roots, we make a commitment: we are not trying to understand the entire graph blindly, but to explore what can be reached and discovered from known anchors.

This view immediately raises the question: how do we best represent such a rooted graph? There is no universally optimal way to store a graph. Sparse graphs benefit from adjacency lists, dense ones may do better with matrices, and large-scale graphs might be stored in files or streamed from a database. The rooted graph abstraction allows us to factor out the representation details and focus on what matters: the reachable structure from a set of entry points.

In doing so, we create a flexible interface for algorithms. An algorithm that operates on rooted graphs needs only to know two things: how to obtain the roots, and how to get the neighbors of a given vertex. Everything else (the storage, the indexing, even the vertex types) becomes an implementation detail. This minimal contract is sufficient to power sophisticated traversals, verifications, and ultimately the core mechanisms behind model-checking.

In this chapter, we will progressively build this abstraction, beginning with simple, explicit graphs, and moving toward more expressive and efficient representations. Along the way, we will isolate our traversal algorithms from specific data structures, creating a flexible foundation for the rest of the book.

Expanding the Rooted Graph Concept: Extrinsic vs. Intrinsic Graphs

The notion of a rooted graph brings us a step closer to modular, general-purpose traversal algorithms. But it also opens the door to a deeper realization: not all graphs are known in advance.

Some graphs are extrinsic: they are explicitly represented, stored in memory or on disk, with their vertices and edges fully known before any traversal begins. These are the typical graphs that one might find in textbooks or programming assignments: adjacency matrices, edge lists, and hash maps. In such cases, all of the data is available up front, and the graph is simply a static data structure to be navigated.

However, many graphs we care about in model-checking are intrinsic. They are not fully constructed before use, nor are they even necessarily finite. Instead, these graphs are defined procedurally. Their structure is revealed step-by-step as we traverse them, with each expansion generating new nodes and edges on the fly. Think of the state space of a program: it is often far too large (or even infinite) to be built explicitly, yet we can compute the successors from any given state.

To make this concept more concrete, consider the example of walking a social network graph using internet requests. Suppose you start from a single user and wish to explore their connections: friends, friends of friends, and so on. Each node in the graph represents a user profile, and edges represent "friend" relationships. But the graph is not known in advance. Instead, each node's neighbors are discovered by querying a server for that user's friends. This is a classic intrinsic graph: its vertices and edges are fetched lazily, on-demand, during traversal. If the traversal stops early (e.g., after finding a particular person or after a certain depth), large parts of the graph remain unexplored and unmaterialized.

This is where the rooted graph abstraction shines. By requiring only two capabilities from a graph, (1) the ability to provide a set of roots, and (2) the ability to compute the neighbors of a vertex, we enable traversals that work seamlessly over both extrinsic and intrinsic graphs.

This abstraction lets us unify a broad class of graphs under a common interface. Whether the graph is a static list of nodes and edges read from a file, or a dynamic exploration of system states driven by simulation or symbolic execution, the traversal algorithm sees only the operations it needs.

In later sections, we will see how this perspective allows us to apply the same core traversal logic to a wide range of applications: from solving games like the Tower of Hanoi, to verifying reachability properties in software models. The rooted graph interface becomes the contract between the traversal algorithm and the underlying system—regardless of whether that system is fully known or just gradually revealed.

This perspective, of graphs not just as data, but as behaviors, is foundational to the rest of the book.

A Rooted Graph and an Explicit Graph Data Structure

A graph is defined as a tuple G=(V, E) where V is an arbitrary set of vertices, and E is a binary relation between the elements in V.

For technical reasons, that will become apparent later, we will allow both self-loops and duplicate edges.

For our purposes, we enrich the previous graph definition with R ⊆ V the multiset of roots of the graph. The roots of a graph are the vertices that provide access to the connected components of the graph. Sometimes R can be just a set, however, the more relaxed multiset concept allows for simpler, less constrained implementations (a list of nodes for instance).

Thus a rooted graph RG is defined as RG=(V, E, R).

Dictionary-based Rooted Graph

To make it simple, we will represent the rooted graph structure by encoding the graph as an adjacency list using a dictionary. The keys of the dictionary will be the vertices of the graph. To each vertex we will associate a list of nodes, which are directly reachable from the vertex.

graph = {

1: [2, 3],

2: [3, 4]

}

To obtain the rooted graph structure we complement the dictionary with another list of vertices, the roots.

roots = [1, 2].

The rooted graph structure is then obtained by encapsulating these to fields in an object. Let's first define a DictionaryRootedGraph class, which allows building the objects that we need.

class DictionaryRootedGraph:

def __init__(self, graph, roots):

self.graph = graph

self.roots = roots

With this, we already have a small domain-specific language (embedded in Python), which allows us to build rooted graphs. Let's see an example

graph1 = DictionaryRootedGraph(

{

1: [2, 3],

2: [3, 4]

},

[1, 3]

)

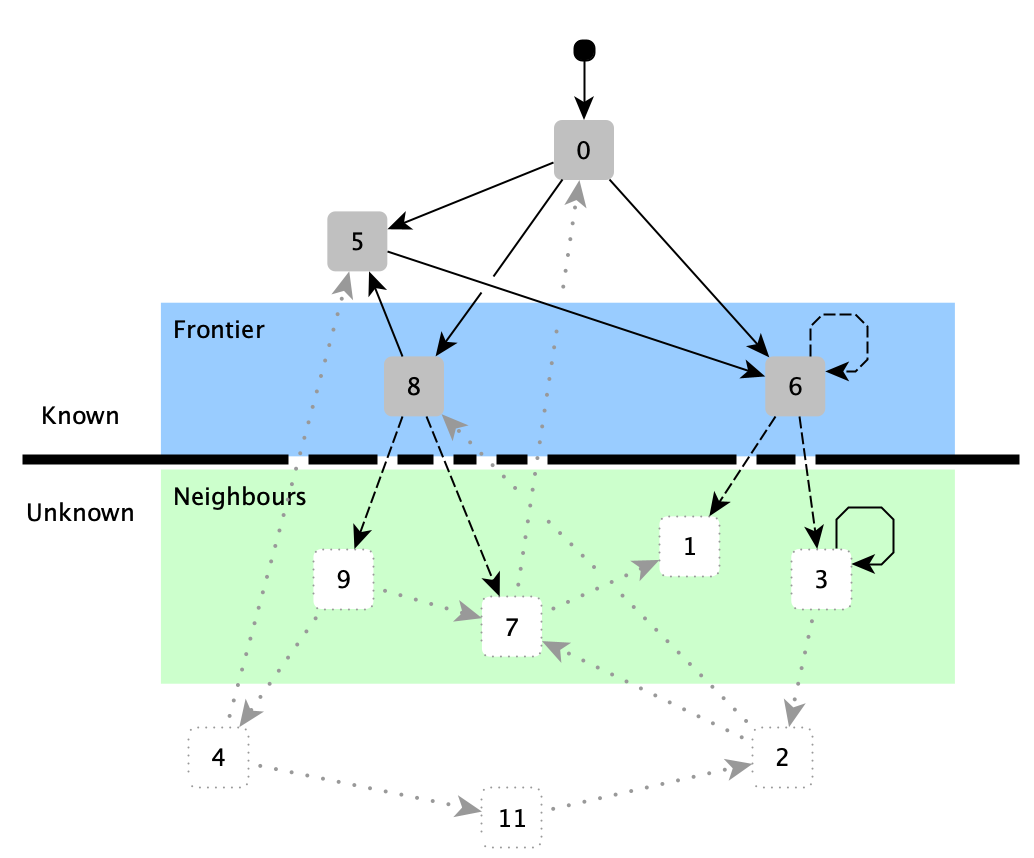

Breadth-First Traversal

{: width="400" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

{: width="400" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

traversal K {} = K

traversal K {x} ∪ F = traversal K F if x ∈ K

traversal K {x} ∪ F = traversal ({x} ∪ K) ((neighbors x) ∪ F) if x ∉ K

dfs K [] = K

dfs K (x::L) = dfs K L if x ∈ K

dfs K (x::L) = dfs ({x} ∪ K) ((neighbors x) ++ L) if x ∉ K

bfs K [] = K

bfs K (x::L) = dfs K L if x ∈ K

bfs K (x::L) = dfs ({x} ∪ K) (L ++ (neighbors x)) if x ∉ K

{: width="200" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

{: width="200" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

breadthFirstTraversal(rootedGraph):

I = True

K = ∅

F = []

WHILE F ≠ ∅ ∨ I DO

N = IF I THEN rootedGraph.roots ELSE rootedGraph.graph[F.dequeue()]

I = False

FORALL n ∈ N

IF n ∉ K THEN

K = K ∪ {n}

F = F ∪ {n}

RETURN K

NOTE: For implementing a set in Python use the set data structure.

NOTE: For implementing the FIFO queue in Python use the deque (Double-Ended Queue) data structure data structure. The deque is a list-like sequence optimized for data access near its endpoints.

Implement this algorithm in Python, and test it. Don't forget to use the debugger to understand what is happening. Amongst your tests think of edge cases for instance:

breadthFirstTraversal(DictionaryRootedGraph())breadthFirstTraversal(DictionaryRootedGraph({}, nil))breadthFirstTraversal(DictionaryRootedGraph(nil, []))breadthFirstTraversal(DictionaryRootedGraph({1: nil}, []))

Fix the algorithm to pass all tests.

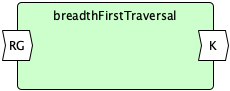

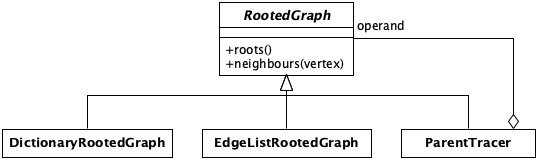

Abstracting Over the Graph

Why is the algorithm polluted with the implementation details of the DictionaryRootedGraph?

The key idea here is to look at the algorithm implementation and try to abstract over the queries on the DictionaryRootedGraph data structure by introducing methods, which will hide the data structure-specific details. We need to analyze the algorithm to understand what queries it performs on our data structure. In our case, the answer is rather simple since our breadthFirstTraversal uses the rootedGraph only at line 6, where performs two queries:

- If we are at the beginning (during the initialization phase), we need the roots of the graph - our entries in the graph.

- In the subsequent steps, for any vertex

vobtained from the frontier (F.dequeue()) we need to obtain its neighbors (the vertices that we get by following the edges starting atv).

Let's add these two methods to the DictionaryRootedGraph class, and then update the breadthFirstTraversal to use these methods, instead of directly using instance variable accesses.

class DictionaryRootedGraph:

def __init__(self, graph, roots):

self._graph = graph

self._roots = roots

def roots(self):

return self._roots

def neighbors(self, vertex):

return self._graph[vertex]

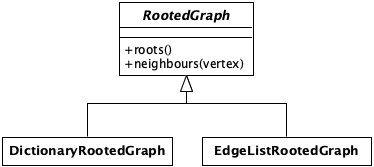

Different Data Structures

Let's say now that we don't like this rooted graph implementation because I have better data-structure implementations:

- for dense graphs (graphs with many edges) a Matrix (a bitmap) representation will be more compact.

- for large graphs with few edges, a sparse matrix encoding of the graph is more compact.

- storing the edges explicitly in a list is easy to parse.

To allow our algorithm to work with different encodings of the graph

Based on this analysis, we can introduce the abstract concept of RootedGraph that will encapsulate (group together) these two functions.

class RootedGraph:

def roots(self): pass

def neighbors(self, vertex): pass

NOTE: By inheriting from ABC and adding the @abstractmethod annotation we can ensure that the RootedGraph abstract class cannot be instantiated directly.

Python uses the duck-typing principle: "If it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck".

Following this principle, in our case, that means that any object that implements the roots(self) and next(self, vertex) methods are considered implicitly as instances of the RootedGraph abstract class. Furthermore, we do not need to define the RootedGraph abstract class at all. Nevertheless doing so greatly improves the readability of the code, as the abstract class clearly defines the public API of any RootedGraph instance. To be even more explicit we can explicitly define the DictionaryRootedGraph class to be an instance of the RootedGraph abstract class.

class DictionaryRootedGraph(RootedGraph):

The EdgeListRootedGraph is a different data structure that can represent the graph with a simple list of edges. The edges in the list are encoded as a Python tuple (source, destination), where the source object represents the source vertex of the edge and the destination object represents the target vertex of the edge.

Besides the edge list, our `RootedGraph`` needs the roots of the graph, we will represent them as a list as earlier.

Create the EdgeListRootedGraph

Here is a simple graph

graph = EdgeListRootedGraph(

[

(1, 2),

(1, 3),

(2, 3),

(2, 4)

],

[1,3]

)

What do we need to do so that we can use our BFS algorithm with this new data structure?

What are the differences between the DictionaryRootedGraph and the EdgeListRootedGraph?

The EdgeListRootedGraph instances are easier to create from a file containing the roots and the edge list.

1 3 #roots

1 2

1 3

2 3

2 4

Write a reader factory that creates an EdgeListRootedGraph from such a file.

{: width="400" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

{: width="400" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

More Generic Vertex Types

Up until now, we have used only integer objects to represent the graph vertices. But in the long run, we will want to handle generic objects.

Try creating a graph of Persons(first_name, family_name) identified by their name. The relations in the graph represent that a Person knows another Person.

Run the previous reachability algorithm on this graph. If we have a relation Person(a, b) -> Person(a, b) what is the result of the reachability query? Why do we have Person(a, b) twice in the result? How can we fix that?

Object Identity versus object Equality, and the set implementation in Python.

To solve this problem we need to enrich our objects with a domain-specific notion of equality. What makes two Person instances equal?

class Person:

...

def __eq__(self, other):

...

def __hash__(self):

...

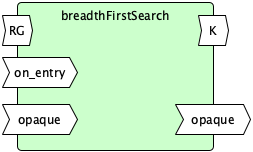

Breadth-First Search

{: width="200" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

{: width="200" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

breadthFirstSearch(graph, on_entry, opaque):

I = True

K = ∅

F = []

WHILE F ≠ ∅ ∨ I DO

N = IF I THEN graph.roots() ELSE graph.neighbours(F.dequeue())

I = False

FORALL n ∈ N

IF n ∉ K THEN

terminate = on_entry(n, opaque)

IF terminate THEN

RETURN (opaque, K)

K = K ∪ {n}

F = F ∪ {n}

RETURN (opaque, K)

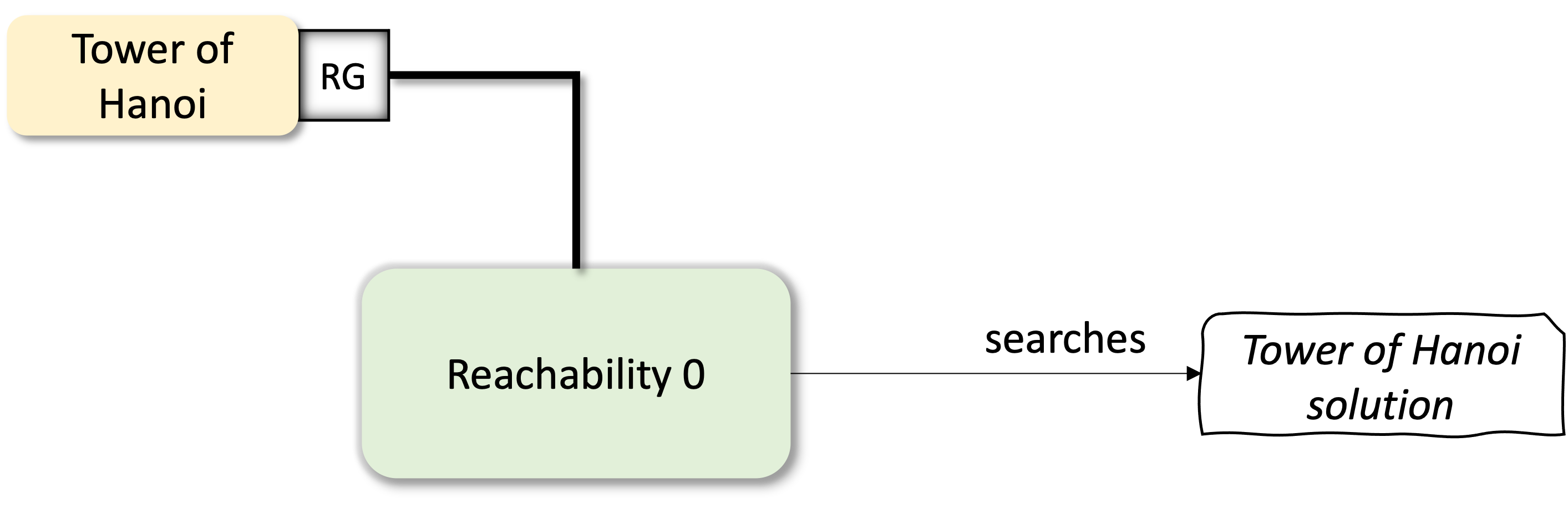

Intensional Graphs: Hanoi Example

{: width="400" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

{: width="400" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

Up until now, we have used only extensional graph representations. But there is no fundamental limit precluding us from using also intensional graph representations. These are graphs that are defined by giving a procedure that can be followed to obtain the graph dynamically on request. At this point, we will start to see the power of our query-based graph manipulations. Here instead of enumerating all the vertices and edges of the graph, we will provide smart implementation of the roots and neighbors methods to generate special graphs programmatically that will then be analyzed by our algorithms.

To make this section a bit concrete we will create a NBits game. The aim is to encode the game state as graph vertices and the game actions, that link two game states, as edges. After encoding the game rules we will look for the solution by simply calling our breadth-first search algorithm.

class NBits:

def __init__(self, n, ini: list):

self.n = n

self.ini = ini

self.accepting = accepting

def roots(self):

return self.ini

def neighbors(self, configuration: int):

targets = []

for i in range(self.n):

if ((configuration >> i) & 1) > 0:

target = configuration & ~(1 << i)

else:

target = configuration | (1 << i)

targets.append(target)

return targets

Now we have these steps to follow:

- Define what is a configuration

def __eq__(self, other):def __hash__(self):

- Define the rooted graph API

- what is the list of roots?

- write an algorithm that generates the neighbors of a given configuration

- Define the query

if __name__ == '__main__':

nbits = NBits(10, [0])

(target, k) = bfsSearch(nbits, lambda x: x == 5)

Exercise:

- Implement Tower of Hanoi Game

Practical situation: Going beyond simple search. Giddy, Jonathan P., and Reihaneh Safavi-Naini. "Automated cryptanalysis of transposition ciphers." The Computer Journal 37.5 (1994): 429-436.

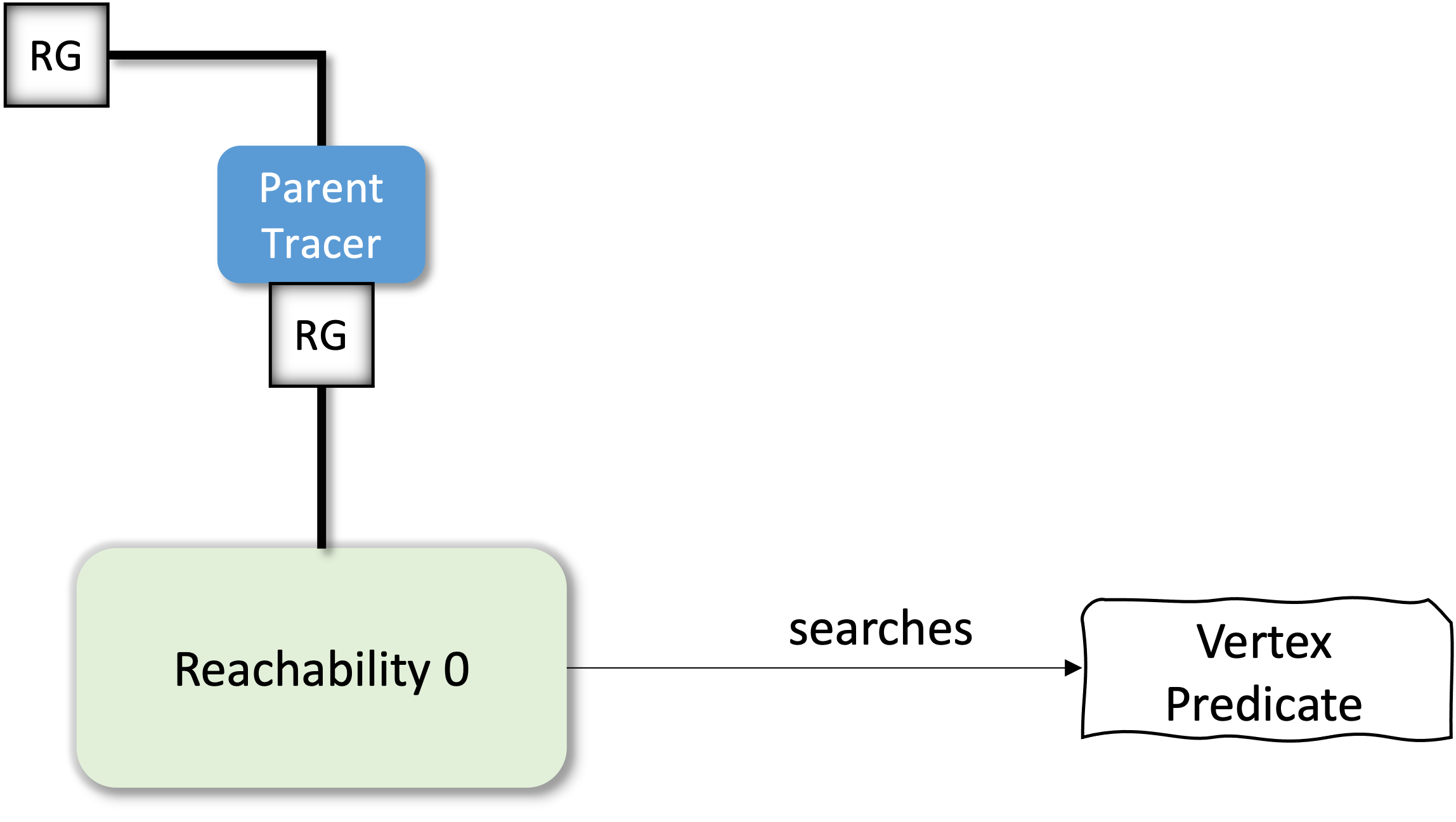

This is great, but, how did we get to this solution?

Building the Trace

{: width="400" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

{: width="400" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

{: width="400" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

{: width="400" style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto"}

class ParentTracer(RootedGraph):

def __init__(self, operand, parents=None):

self.operand = operand

self.parents = {} if parents is None else parents

def roots(self):

neighbours = self.operand.roots()

for n in neighbours:

self.parents[n] = []

return neighbours

def neighbors(self, vertex):

neighbours = self.operand.neighbors(vertex)

for n in neighbours:

if self.parents.get(n) is None:

self.parents[n] = [vertex]

return neighbours