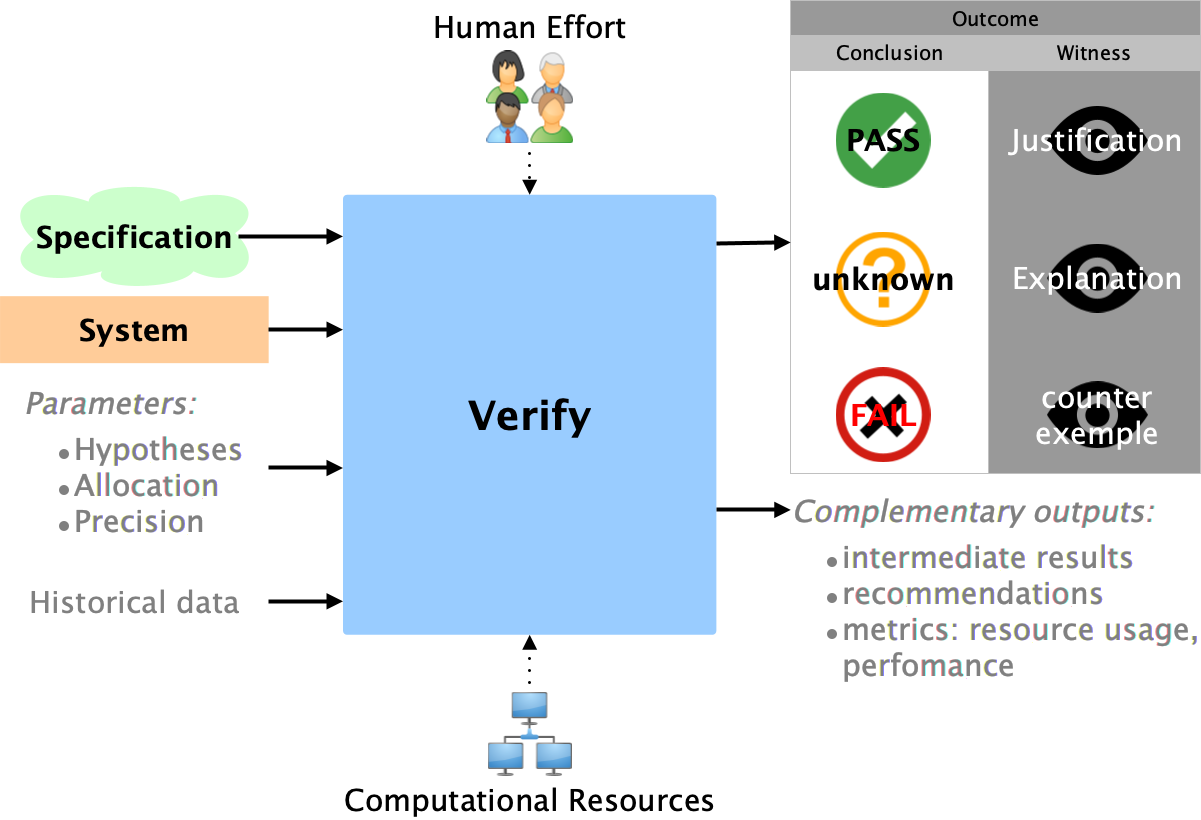

Verify Function Context Diagram

Context

In the development and deployment of complex systems, verifying whether a system meets a given specification is fundamental to ensuring its correct and reliable operation. Specifications outline the intended functionality, safety requirements, and other performance criteria that a system must meet. Verifying a system against these specifications is vital not only to ensure quality and correctness but also to comply with regulatory standards, minimize risks, and provide confidence to stakeholders that the system will operate as intended. Given the complexity of modern systems, verification can range from manual, human-driven checks to fully automated, computationally intensive processes.

Problems

System verification is inherently challenging due to the complexity of specifications and the variety of system behaviors. Verifying that a system model satisfies its specification is often resource-intensive and may require sophisticated techniques to produce reliable conclusions. Additionally, verifying systems under realistic constraints — with finite time, computational power, and human resources — introduces further complications. A key challenge is ensuring that the specification accurately reflects the specification author’s intent, requiring careful concretization and idea-capturing to translate high-level concepts into explicit, verifiable requirements. Equally fundamental is the need to obtain a faithful model of the actual system through an abstraction process that accurately reflects the system’s behaviors and structure. Verification outputs are critical for decision-making and need to be clear, actionable, and trustworthy. Moreover, the adversarial context, where malicious actors may attempt to bypass or exploit verification steps, demands additional resilience from the verification process itself.

Purpose of the Verify Function

The verify function is designed to systematically evaluate whether a system model satisfies a given specification. The function uses both human and computational resources in varying proportions, depending on the verification needs and resources available. By processing inputs such as specifications, system models, verification parameters (hypotheses, resource allocation, and precision), and optionally, historical data, the function aims to deliver reliable outcomes. The main goal is to determine whether the system meets its requirements, doesn’t meet them, or if the result is indeterminate due to certain limitations. It also provides structured feedback in the form of verification results, intermediate insights, and recommended actions to aid decision-makers in addressing verification findings.

Description of the Verify Function

A generic verify function context diagram is shown in the following figure:

The verify function operates as follows:

- Primary Inputs:

- Specification: The set of requirements and constraints that define acceptable system behavior.

- System Model: A representation of the system to be verified, which may include detailed structures, behaviors, and states.

- Verification Parameters: Settings that define the scope and depth of verification, including assumptions, resource allocations, and precision requirements.

- Historical Data (optional): Previous verification outcomes that help refine the process.

- Verification Process:

- The function applies verification techniques with varying degrees of human intervention and automation. On one end, manual verification involves human inspection without computational support. On the other, fully automated verification leverages algorithms and computational power to achieve the results with minimal human input.

- Primary Outputs:

- The verification output is structured as a tuple

(conclusion, witness), with the following three possibilities:- (OK, justification): The system satisfies the specification, with a justification explaining the compliance. In some cases, this justification may be unavailable.

- (Fail, counter-example): The system does not meet the specification, with a counter-example highlighting the failure. Sometimes, the counter-example might be missing.

- (Unknown, explanation): Verification cannot determine compliance, with an explanation outlining the reasoning. This explanation might include traceability details, such as assumptions or verification paths. Sometimes, the explanation itself might be unknown if the limitations of the verification are unclear.

- The verification output is structured as a tuple

- Complementary Outputs:

- Intermediate Results: For complex systems, verification may take time. Periodic checkpoints or incremental findings allow stakeholders to monitor progress or understand partial conclusions.

- Suggested Actions & Recommendations: When verification results indicate a failure or uncertainty, the function can suggest next steps, such as revising the model or exploring specific areas of the specification.

- Metrics: Information on verification performance, resource usage, and complexity helps optimize future verification tasks and provides insight into verification robustness.

Challenges

The verify function faces several key challenges:

-

Resource Constraints: Balancing human and computational resources effectively is challenging, especially for complex systems requiring high precision or thorough exploration of states.

-

Scalability and Complexity: As system models grow in size and complexity, verification becomes exponentially more challenging, sometimes resulting in incomplete justifications or missing counter-examples.

-

Traceability and Transparency: Verification results must be traceable to specific parameters and assumptions to be useful. This requires detailed reporting and logging, which can be difficult to maintain in large systems or automated processes.

-

Handling Ambiguity: Specifications may sometimes be ambiguous or incomplete, leading to “Unknown” conclusions. Verification must have mechanisms to report such ambiguities clearly, ensuring they are addressed in future verification cycles.

-

Security and Robustness: Adversarial stakeholders may attempt to bypass or manipulate the verification process. The verification function must be resilient against such threats, ensuring that results cannot be tampered with and that outputs accurately reflect the system’s compliance status.

-

Specification Intent and Explicitation: While typically considered outside the scope of the verification function, a significant challenge in verification is ensuring that the specification truly captures the intent of its authors. This process of explicitation—transforming ideas into concrete, precise requirements—requires careful thought and alignment before verification can be meaningfully applied.

-

Faithful System Model Abstraction: Another prerequisite for reliable verification, generally considered external to the verify function, is obtaining a system model that faithfully represents the actual system. This abstraction process, capturing essential behaviors and structures without omitting critical aspects, is essential to avoid mismatches between the model and the real system that could compromise verification results.

Certainly. Here’s a section that incorporates these thoughts and presents the elements you consider orthogonal to the core purpose of the verify function:

Considerations on the Context Diagram

While the presented context diagram for the verify function provides a generic view, there are several aspects included that seem somewhat orthogonal to the function’s core purpose:

-

Historical Data: Although historical data can be helpful, it ideally should be collected by an encapsulating process or function that manages data over multiple verification cycles. Rather than feeding historical data directly into the verify function, it could be better organized as a higher-level process feeding back relevant insights into the function via refined verification parameters. This separation would help keep the function focused on the immediate verification task rather than managing historical context.

-

Intermediate Results: The generation of intermediate results is another element that feels tangential to the primary verification objective. In principle, intermediate insights could be obtained by externally observing or inspecting the state of the verification process as it runs, rather than being managed as an explicit output of the function. This approach keeps the function streamlined and allows external observers or monitoring systems to capture and log incremental states without overcomplicating the function itself.

-

Metrics (Resource Usage, Performance, etc.): Metrics such as resource usage, memory consumption, and performance statistics are similarly external to the core purpose of verification, which is focused on evaluating compliance with specifications. These metrics are more aligned with observing the underlying resources—human or computational—that facilitate verification. Monitoring systems could observe and log this information independently, through an external “resource substrate,” rather than having the verification function track it directly. This way, the verify function remains focused, with performance metrics collected via external instrumentation.

These elements (historical data, intermediate results, and resource metrics) could be observed and managed at a meta-level, perhaps through something akin to a digital twin or a wrapper for the verify function. Such a meta-layer could provide the necessary observability and memory to track historical runs, monitor ongoing state, and capture resource data without complicating the primary function. In this sense, these elements could be viewed as meta-level components that, while useful, are not part of the core verification logic itself.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: